What was the world's first language?

- Vyvyan Evans

- Mar 28, 2024

- 3 min read

The idea that all the spoken languages of the world directly originated from a single language is known as monogenesis. Today there are around seven thousand spoken languages. And these languages can be grouped into so-called language families, groupings of languages that share certain lexical, grammatical and phonological similarities, as well as being connected historically and usually geographically.

We know, today, based on genetic dating that our species, Homo sapiens, originated from a group of around 10,000 individuals in south-eastern Africa around 170,000 years ago, plus or minus 30,000 years, which is the margin of dating error.

An increasing consensus of researchers also agrees that our species had the ability to produce spoken language for all of its history. The ability to produce spoken language may have been in evidence with ancestral humans, Homo heidelbergensis, half a million years ago. And it is increasingly believed that other now extinct early human species, such as Homo neanderthalensis (‘Neanderthals’) may also have had a capacity for some form of (spoken) language.

Given that other, earlier species of ancestral humans, such as Neanderthals (may have) had language, then clearly, it is plausible that our species possessed some form of spoken language for its entire history.

The earliest modern human language(s) likely emerged in Africa, pre-dating the out-of-Africa dispersion of Homo sapiens, around 100,000 years ago onwards. There are two compelling reasons for suspecting this.

First, Africa has the greatest concentration of languages in the world. Africa has around two thousand native languages, and by some counts perhaps as many as three thousand. Indeed, Nigeria alone has as many as five hundred distinct languages.

Second, as the ‘vocabulary’ of sounds that make up a language, technically known as phonemes, evolve and change over time much more slowly than vocabular or grammar. Hence, the languages with the greatest number of phonemes are likely to be older than those with fewer.

The languages with the greatest number of number of phonemes are found in Africa, with up to 144 distinct phonemes. The smallest inventories of phonemes are found in languages spoken in regions such as Oceana and South America. These geographical regions were also among the last regions of the world to be colonized by humans. For instance, Hawaiian has just thirteen phonemes.

That said, none of this entails that all of the world’s languages are directly descended by a single language, let’s call it Proto-World, spoken 170,000 years ago in Africa. There are two reasons for this.

First, there are so-called isolate languages, such as Basque, which do not appear to be obviously related to any other language. These isolates are what we might think of as stand-alone languages—ones that cannot be obviously placed within a language family by linguists.

And second, it is now clear that human communities can, within three generations or less, produce fully-formed naturally-occurring languages from scratch. Such instance have best been documented in cases of isolated communities, especially among sign language users—language is, after all, not restricted to a specific channel for purposes of us. (A language can be conveyed through speech, gesture, writing, and visual representation--such as Blisssymbolics). In principle, all that is required to encode language is a physical representation—a sign. But what is clear is this doesn’t have to be sound.

A famous case in point is the Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (ABSL) which is a village sign language. This sign language developed, within an isolated village community, into a fully-fledged language, with a functional grammar and vocabulary system in less than three generations.

The upshot of all this is that asking whether there was a single language from which all others are directly descended, is a misnomer. It is better to ask, what was the world oldest human language? And alas, without a time machine, what remains are reconstructions using methods from historical linguistics, including statistical methods, to help us produce approximate sketches.

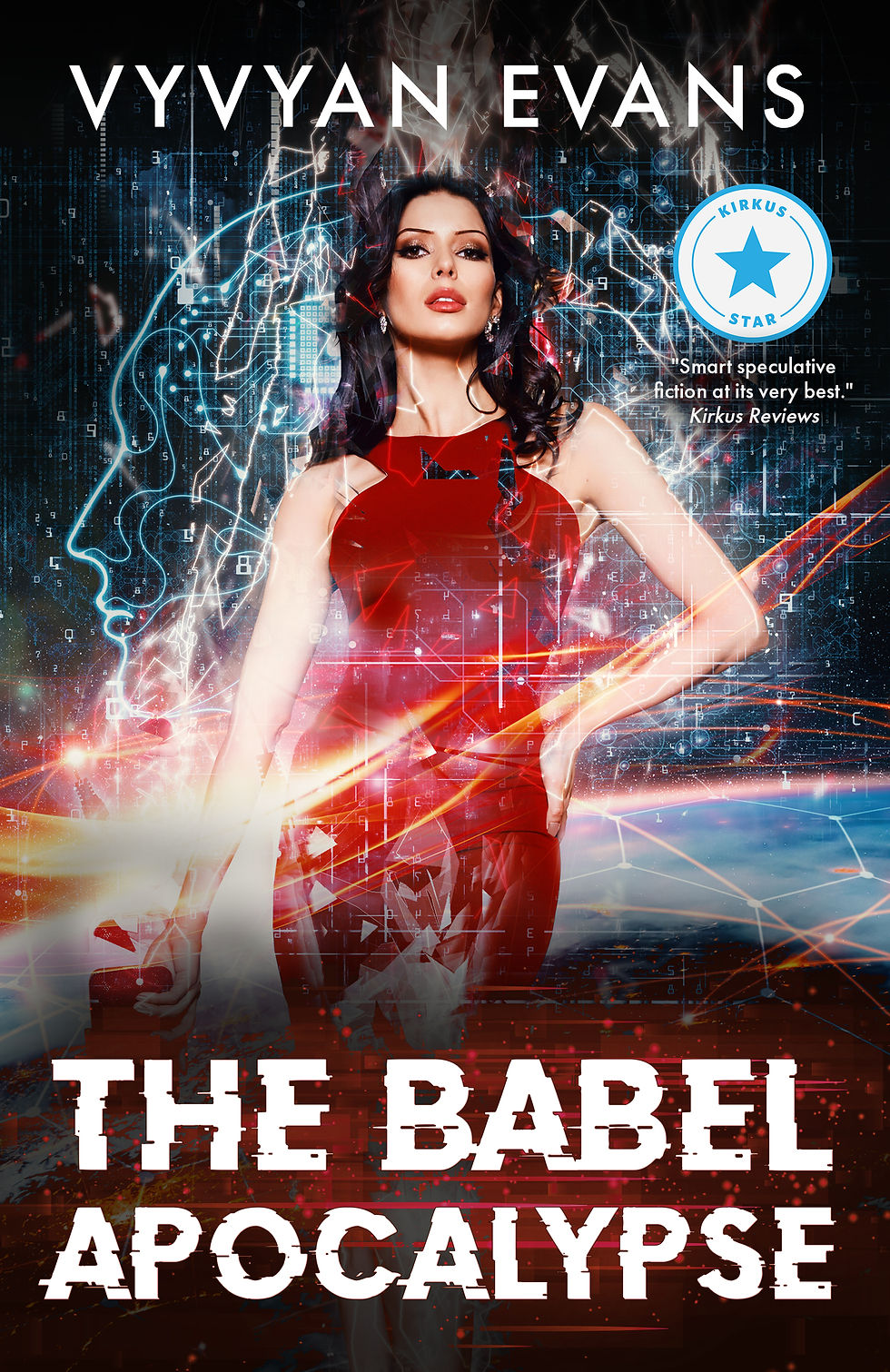

In the realm of speculative fiction, we can do better than make sketchy guesses. We can offer fully world-out proposals. And this is exactly what I am doing in my Songs of the Sage book series. Over the course of the six books that make up the series, I explore (among other things) the nature and origin of language, examining a genesis far older than modern humans, as well as one that is much more exotic.